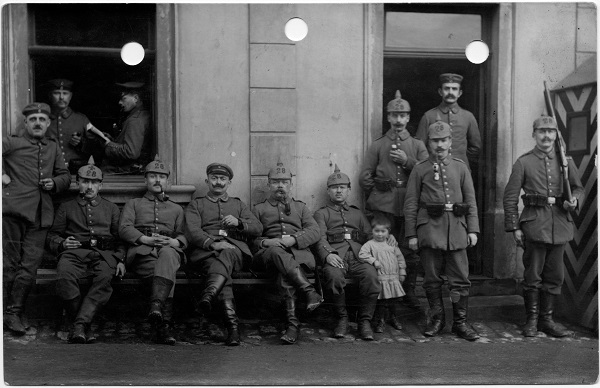

Troisvierges railway station during the war with German soldiers and sentry;

Credit: Photos provided by David Heal

Troisvierges railway station during the war with German soldiers and sentry;

Credit: Photos provided by David Heal

Chronicle.lu has teamed up with local author and tour guide David Heal of Luxembourg Battles for a historical series.

Based on David Heal's extensive research spanning several decades (and documented in the form of place-name index cards), the series aims to present interesting local historical events and facts linked to places in (and around) Luxembourg.

Next up is a look at the history of one of the most northerly towns in Luxembourg: Troisvierges. The name was originally "Ulflingen" (German) - or "Ëlwen" in Luxembourgish. When the railways arrived in Luxembourg, the tourist industry followed. The Ulflingen town council may have thought that that name was unlikely to attract the tourists, so the name was changed to the more romantic Troisvierges. Other sources say the French name was adopted in the 17th century when Walloon pilgrims began using it to refer to the three saints Fides (Faith), Spes (Hope) and Caritas (Charity). A bronze statue of the three graces can still be found outside the town hall.

Possibly the most significant event of the town's history took place on the evening of 1 August 1914, when they were invaded by the German army. As David explained, the town Gendarmerie sergeant recounted in a report that he heard some vehicles going past and saw a German army lorry followed by a staff car head in the direction of the station. One of his gendarmes went to see what it was all about and found the officer-in-charge demanding that the clerk at the station hand over the telegraph and threatening to have him shot if he did not. The clerk dropped the telegraph on the floor and broke it. The gendarme asked why they were in Luxembourg - a country neutral by treaty and with Germany as one of its guarantors. This must have been embarrassing, noted David, as the officer promptly told the gendarme that he would be shot.

In the meantime, a group of soldiers had gone through the tunnel to the north of the station and were busily tearing up the line from Aachen (now a cycle track) from where it joined the main line from Liège. They had torn up at least 100 metres when an officer arrived from Germany with a telegram. The officer-in-charge read it and gave orders for the rails to be replaced, and then they all went home - to Lengeler just over the border in what is now Belgium but was then Germany.

What was going on? The second telegram was as a result of a telephone call in which the German and British Foreign Ministers had managed to completely misunderstand one another, so the war which was supposed to start at 18:00 on 1 August was put off until 06:00 on 2 August - when they came back. Why pull up the railway? A complete mystery then and now, according to David. Even more mysterious as they did not pull up the rails the next morning. It could have been a complete disaster, added David. The Aachen line was due to bring troop trains into Luxembourg at ten minute intervals. The line had been torn up to a curve with a cutting. The trains would have crashed as they came round it and found no rails. David spoke of the possible carnage - even more so if the trains had caught fire. They also would have blocked the Liège line. The Germans would have sabotaged their own invasion.

The entire German invasion of Luxembourg was so that they could use the railways, which gave easy access to France. By the end of the war, the Luxembourg system was the most important for Germany on the whole Western Front, noted David.

There is a lot more to this story, which gets increasingly mysterious as one investigates it, but space does not permit the whole story to be explained.

Today, the station is still there as it was in 1914 (with a smart new cladding). All the buildings are the same as in 1914, and even the remains of the old turntable can be seen in the marshalling area.

David advised anyone wanting to visit to get some maps and go for a walk - there are some "excellent" walks there. Up the railway line and one will come to a tunnel into Germany which is now a bat sanctuary, which is why there is a diversion of the cycle track, and an electronic display board explaining which bats can be found there. Visitors can also follow a signposted walk commemorating the route which the escapers from the Nazis used to go to Belgium, France, Portugal and Britain eventually. However, Belgium has cut down a part of the forest, added David, so care needs to be taken not to get lost - the signs are still there, but simply pushed into the ground, and point in every direction.