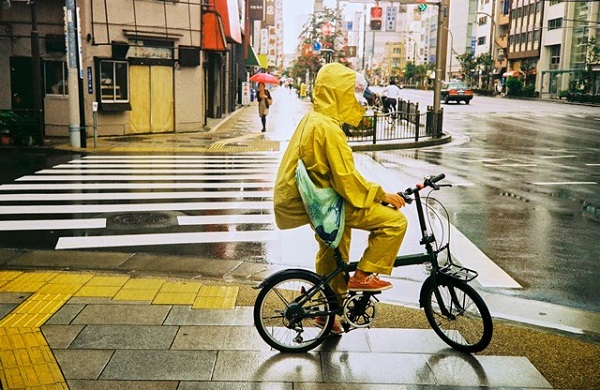

It is common advice - build an emergency fund equal to between three and six months of take-home pay in case of unexpected expenses. Often also known as “rainy-day funds” because money is set aside for unfavourable conditions, they are the bedrock of personal financial planning.

For many, unfavourable conditions have arrived. It is raining. Work and income have dried up. Many people face not only a Covid-19 crisis but a liquidity crisis. The liquidity crisis can be reduced by taking money from the rainy-day fund. That is what it is there for.

However, there are four problems with this.

First, nobody can be sure how long this crisis will last.

Second, there is a presumption that many people have rainy-day funds. Survey evidence suggests few people have a sizeable emergency savings buffer.

Third, there is a presumption that a key motive for why people save is as a precaution against income shocks. But if this is not the case, those who have savings may not be willing to reduce them in the current circumstances.

Fourth, a noticeable percentage of those who have savings will be reluctant to reduce them because they are more emotionally wired to save rather than to spend. These people will find it difficult to reduce savings.

Unpredictable forecasts

Usually, rainy-day funds are set up to meet emergencies that have a known cost. For example, the cost of an urgent car repair is likely to be known with some accuracy so can be accommodated by a given rainy-day fund. The current situation is less predictable. The rain may last for some time.

Given this, the best way to use rainy-day funds is unknown. But that is not an excuse to avoid making a plan. Figure out your and your household’s spending priorities. Any plan under current circumstances is likely to be inexact. However, as John Maynard Keynes said: “It’s better to be roughly right than precisely wrong.”

You may as well make this plan now. Do not put it off. Procrastination has been shown to lead to financial problems.

Tightwads and spendthrifts

Even if people have saved for uncertain events, they may find spending those savings emotionally difficult. It may be that those who save tend to be cautious. Some may even find spending difficult, to the point that they spend less than they would ideally like to spend. They are emotionally conflicted by spending. Such people can be called “tightwads”. On the other hand, there are those who spend more than they would like. These people can be called “spendthrifts”.

A 2007 paper studying spending attitudes in the USA found that most people (60%) are not conflicted by their spending behaviour. They are neither tightwads nor spendthrifts. However, 24% recorded as tightwads and 15% as spendthrifts. The paper did not trace these groups to saving behaviour. Nevertheless, there is evidence that about one-in-five people (20%) are reluctant to spend. If so, spending their rainy-day fund will be difficult.

Waiting out the rain

How people will react to the current situation is as unpredictable as the outcome of what we are going through. We should not assume people will run down their savings. They may simply wait to spend again once the rain is over.

This piece is based on an article originally published on think.ing.com.