A long way down...;

Credit: Jazmin Campbell

A long way down...;

Credit: Jazmin Campbell

Few people can say they have explored the interior of a road bridge, never mind one as impressive and historically rich as Luxembourg City’s Grand Duchess Charlotte Bridge. On Thursday morning, however, members of the Luxembourgish press were fortunate enough to do just that.

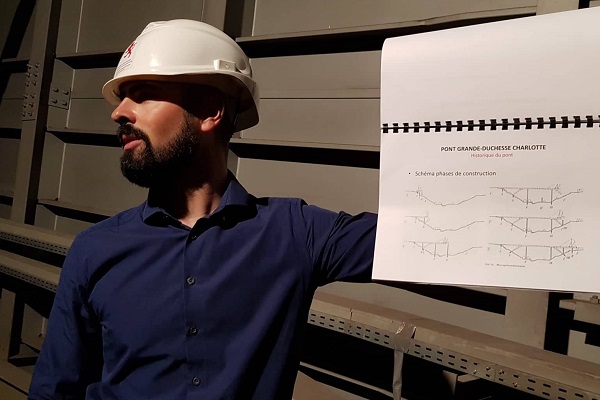

During a private visit organised by Luxembourg’s Roads Administration, over a dozen of us donned bright orange safety helmets, crossed the Red Bridge (“Rout Bréck”, as it is known to locals for its distinctive paintwork) from Kirchberg to Limpertsberg and climbed into the depths of the 4,900-tonne structure’s steel body.

Once inside, our guide Gilberto Fernandes, director of the Artwork division of the Roads Administration, began by explaining the structure and origins of the bridge, which celebrated its 56th anniversary last month. Indeed, the story begins in 1957 in the context of the development of the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC), predecessor of today’s European Union. At this time, Luxembourg City was the temporary headquarters of the ECSC and, in a bid to increase the city’s attractiveness in this context, the Luxembourg Government launched a design competition for a new bridge linking the historic centre of the capital (via Limpertsberg) and the until then rather inaccessible and uninhabited Kirchberg plateau. The winning design (out of over 60 submissions) came from German architect Egon Jux.

Construction began with the laying of foundations in 1962 before the arrival of the first section of the bridge from Germany in June 1963. The event was celebrated with a ceremony in the presence of Luxembourg’s then reigning monarch Grand Duchess Charlotte, after whom the bridge is officially named. Construction ended two years later, in June 1965, and the bridge was inaugurated in 1966. The Grand Duchess Charlotte Bridge, an example of a box girder structure measuring an impressive 355 metres in length, 25 metres in width and 75 metres in height, would later undergo a series of renovations in the 1980s and 1990s and again between 2015 and 2018 as part of preparations for the Luxtram network.

What was not addressed during our visit to the bridge was a darker part of the Red Bridge’s history. Indeed, the renovations carried out in the 1990s (specifically 1993) aimed at preventing suicides committed by jumping off the structure: over 100 people have ended their own lives in this way since the bridge’s opening. The sombre issue was perhaps best highlighted by Luxembourgish director Geneviève Mersch’s short documentary “The Red Bridge” (Le Pont Rouge) in 1991. Two years later, the government finally decided to install safety barriers (replaced and reinforced in 2017) to prevent further suicides.

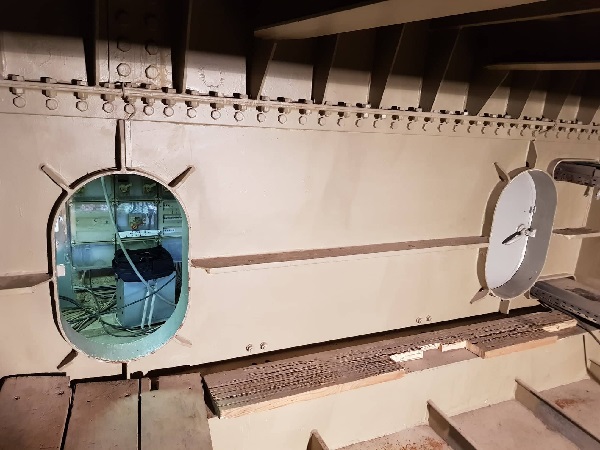

Getting back to the visit itself, the inside of the bridge was, perhaps unsurprisingly, a hollow steel construction; unlike its once-vivid, now-faded red exterior, the inside is mostly an “army green” or grey colour. Less expected were the array of small doors and narrow stairways, some of which we got to crawl into and climb, that make up this internal network. For that’s what it was like in there: a sort of underground network (except you are actually suspended in the air) of steel passageways, pillars and ladders which make it seem like there are several different rooms. These room-like spaces also varied in that some sections of the bridge were broader and higher than others, meaning we had to do some acrobatics to enter and walk around each area - all the while trying to avoid feeling too claustrophobic. Adding to this underground atmosphere was the movement and noises coming from the cars, trams and other vehicles passing above our heads.

During the tour, we walked from one of the construction’s two box girders (one situated in the most northern section of the bridge and the other in the most southern part) towards the mid-section and highest part of the bridge. There, Gilberto Fernandes emphasised how the structure had been built from one side to the other rather than from the bottom upwards, mainly due to the enormous height of the bridge. Looking towards the present day, he pointed out the steel reinforcements put in place in recent years to strengthen the construction from the inside out in preparation for the reintroduction of Luxembourg’s tram network. All that’s left of these latest renovations are a few finishing touches.

As the hour-long exclusive visit came to an end, we walked, crawled and climbed back to the starting point and left with new insight into the (literal) inner workings of one of the capital’s most important structures.