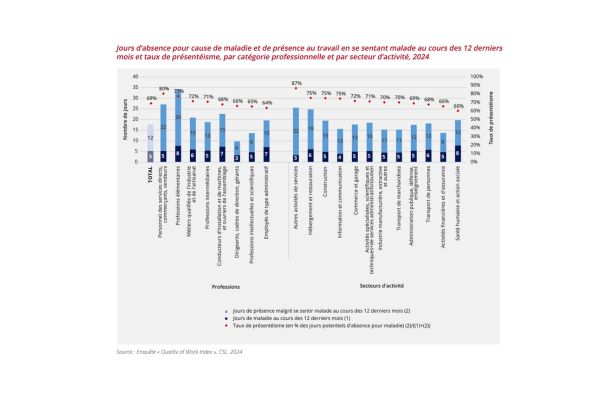

Days of absence due to illness, presence at work when feeling sick, as well as presenteeism rates, by professional category and sector of activity during 2024;

Credit: EcoNews, CSL

Days of absence due to illness, presence at work when feeling sick, as well as presenteeism rates, by professional category and sector of activity during 2024;

Credit: EcoNews, CSL

Luxembourg’s Chamber of Employees (Chambre des Salariés – CSL) recently presented the results of an analysis of presenteeism in the workplace, which showed that employees work an average of twelve days a year while feeling unwell, compared to five days absent.

According to the CSL’s publication, EcoNews, presenteeism is defined as "the behaviour of a worker who, despite physical and/or psychological health problems requiring absence, shows up to work."

The 2024 Quality of Work (QoW) survey, produced by the CSL, included a specific question aimed at assessing presenteeism. According to the results, employees reported working while feeling unwell on average twelve days over the previous twelve months, compared to 5.3 days of sick leave, i.e. employees worked 69% of the days they felt sick. The CSL noted that this demonstrated the predominantly "company-friendly" decision made by employees.

Employees in professions more exposed to difficult working conditions were reported to be particularly affected. Fear of job loss or career setbacks, as well as a poor quality of life at work, also play a crucial role in encouraging sick employees to go to work.

The CSL added that the number of days of sick leave ranged from 3.3 days for executives, senior executives and managers to 7.7 days for elementary occupations (such as housekeepers or labourers), a difference of 4.4 days between the occupations with the fewest and most days of sick leave taken.

In contrast, the number of days present at work despite feeling sick (presenteeism) was six days for managers and executives compared to 26.5 days for elementary occupations, a difference of 20.5 days between these two occupational categories.

The study indicated that the differences between occupations and, to a lesser extent, between sectors are significantly greater in terms of presence than in terms of absence when unwell. Elementary occupations, as well as plant and machine operators and assembly workers, recorded both the highest number of days absent due to illness and the highest number of days present at work while feeling sick. Conversely, managers and executives, as well as intellectual and scientific occupations, were the categories with the lowest number of days absent and also the lowest number of days present.

The highest rate of presenteeism was reported to be among employees in the direct service personnel group, such as cooks, hairdressers, caretakers, as well as shopkeepers and salespeople, who work on average 80% of the days they feel sick. The next highest category was employees in elementary occupations, who had a rate of 77%. The lowest rates were associated with employees in administrative jobs (64%) or those in intellectual and scientific professions (65%). In terms of sectors, "other service activities" such as laundry and dry cleaning, hairdressing and beauty care, funeral services and nonprofit organisations had a presenteeism rate of 87%. This sector also recorded the highest number of days present at work while feeling sick (25.6 days) but also the lowest number of days absent due to illness (3.4 days). The accommodation and catering, construction and information, as well as communications sectors, ranked second with a rate of 75%. This rate dropped to 60% for employees in the human health and social work sectors. Other factors cited as being decisive in the analysis of presenteeism or absence due to illness were specific working conditions such as physical strain or psychosocial constraints, as well as the age of employees or other socio-demographic characteristics.

While the QoW survey provided information on the extent of presenteeism in terms of days, the CSL noted that a publication from Luxembourg’s General Inspectorate of Social Security (IGSS) examined whether employees were totally absent, totally present or whether they alternated between being absent and present at work during their illness (partial presence). According to the IGSS, 85% of employees who were unwell called in sick to work at least once during the year. Among episodes of illness, 49% resulted in total presence, 26% in total absence and 25% in partial presence.

The duration of the illness appeared to play a key role, as the longer the episode, the more employees alternated between absence and presence. Moreover, presenteeism concerned all illnesses, whether chronic or not, and was not limited to mildly disabling conditions. Even for more serious illnesses, the combination of absence and presence was frequent. Employees' decisions reflected a trade-off between the risks to their future health, if they chose to show up to work, and the risks to their job or career, if they took time off. An employee who assumed that their absence could be detrimental was reported to feel obliged to opt for full presence to avoid displeasing others and sending a "negative signal" to the employer. Furthermore, when health deteriorated and episodes of illness progressed, employees tended to go from full presence to partial presence then from partial presence to total absence.

The CSL underlined the importance of rethinking policies to combat absences due to illness. Preventing absences should not result in forcing sick employees to avoid taking time off or to reduce the duration of their absence due to a possible reduction in future income or the potential loss of their job. The financial consequences are often more detrimental for people with lower incomes, less favourable working conditions and a higher risk of illness. For these employees, a phenomenon of presenteeism can develop, increasing the risk of premature withdrawal from the labour market.

The CSL also discussed a scientific review of literature carried out by France's Direction de l'Animation de la Recherche, des Études et des Statistiques (Dares; French Directorate of Research, Studies and Statistics) which revealed that a difficult financial situation influences presenteeism, but also that a good quality of life at work is associated with less presenteeism. However, the opposite is also true: there is more presenteeism when the quality of life at work deteriorates, for example in the event of a heavy workload, irregular schedules or a lack of time or resources. Job insecurity or a risk of job loss also encouraged sick employees to attend work.

Furthermore, the CSL added that there was a risk of stigmatisation of employees when absences were repeated or related to mental health, thereby encouraging employees to be present when they should be absent.

According to the CSL, the consequences of presenteeism include:

- health and long-term absences: at an individual level, presenteeism does not allow sick employees to fully recover, which can also lead to prolonged absences in the longer term. Ignoring current health problems can lead to more serious conditions later on. The spread of illness to other employees could also lead to an increase in sick leave within the company;

- productivity: an employee who comes to work with physical or psychological health problems will perform less well than if they had been in good health. Presenteeism can therefore lead to a drop in individual productivity and errors at work. Collective productivity can also be affected by the possible contamination of other employees;

- costs: potential errors and reduced productivity generate additional costs for the company. According to the scientific literature reviewed by Dares, the estimated costs of presenteeism could exceed those of sick leave. The CSL said the hidden costs of presenteeism, such as the impact on the morale of employees present despite illness, decreased job satisfaction, disengagement, increased turnover and an increased risk that other employees will also feel under pressure and call in sick at work, should be considered.

The CSL concluded by emphasising that employees, on average, go to work when feeling unwell more often than they are absent due to illness. For half of the illness episodes, employees go to work completely, without even partially reporting illness. The results show that presenteeism and taking sick leave varies considerably from one profession or sector to another. While sick leave causes direct and tangible costs for businesses and social security, presenteeism also generates significant costs, in terms of productivity, health, well-being and motivation.

Moreover, the analysis highlighted the need to consider the impacts of presenteeism in strategies aimed at reducing absences from work. Presenteeism is often motivated by the fear of penalties or job loss. Measures aimed at reducing absences, such as increasing the cost of absence for the employee or the risk of being penalised in their career, can therefore encourage harmful presenteeism with multiple consequences. The CSL underlined the necessity to focus efforts on improving working conditions and managing occupational health, paying particular attention to the opinions of employees or their representatives on their quality of life at work. Prevention, non-stigmatisation, improved working conditions, a peaceful work environment, the supportive reintegration of sick people and an effort to understand absences appear to be fundamental to preventing both presenteeism and sick leave.

HOM